Why We Still Need Catholic Schools

They provide a unique educational alternative for disadvantaged kids.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of the City Journal.

On June 30, the United States Supreme Court, in a five-to-four ruling, held that the First Amendment’s Free-Exercise Clause prohibits the government from excluding faith-based schools from school-choice programs. The decision, Espinoza v. Montana, is momentous. Supporters of faith-based institutions, and especially Catholic schools, have long fought for the principle, endorsed by Chief Justice John Roberts’s majority opinion, that preventing such schools from accessing public resources because they are religious is unjust, born of bigotry, and ought to end. That battle, undertaken as early as the 1850s by Catholic bishops—most notably, the fiery archbishop of New York, “Dagger” John Hughes—is now over. But whether the court victory comes in time to help secure the future of urban Catholic schools is another question. Even before Covid-19 shutdowns hit their finances, many were struggling—and a big reason was the emergence of charter schools.

In January 2018, Bishop Martin Holley announced that all Memphis Jubilee Schools—an urban network serving disadvantaged children—would close at the end of the 2018–19 school year, primarily because of financial concerns, and reopen in the fall as charters. The decision, affecting nearly 1,500 students, rocked the Catholic educational world. For decades, the Jubilee network—the “Miracle in Memphis”—had been a bright spot in an otherwise bleak reality facing Catholic schools. Nearly 20 years earlier, Holley’s predecessor, Bishop Terry Steib, had reopened nine previously closed Catholic schools to serve low-income Memphis kids. Steib later added several schools, including the only Catholic high school in Memphis’s urban core, to the network. Almost all the kids attending were poor and paid little or no tuition; most were African-American and Hispanic. And the schools got real results.

Catholic educators put the best face on the charter change. Former diocesan superintendent Mary McDonald, a Jubilee architect, likened the transition to a parent watching a child graduate from college or get married. “Now it’s time for the child to move on and do what is the next best thing in that child’s life. . . . The bottom line is how we can assure that the children are receiving the education they need to give Memphis an educated workforce and lift people out of poverty.” In other words, poor kids in Memphis don’t need Catholic schools because they have charters.

The closure of the Jubilee Schools and their conversion into secular charter schools is part of a trend. As Peter Schuck observed in Why Government Fails So Often, the government’s decision to fund a service can (and often does) “crowd out” other providers of a similar service. The “charter compromise” on parental choice has had exactly this effect, with charters squeezing urban Catholic schools that had long been the best (and often only) alternative to failing public schools for disadvantaged kids. Over the past decade, more than 1,200 Catholic elementary and secondary schools—most located in urban areas—have closed. Enrollment in Catholic schools declined by more than 400,000 students, or 18.4 percent. From a peak of 5.2 million in the early 1960s, Catholic enrollment is down to just over 1.2 million today, and the number of schools has dwindled from just over 13,000 to slightly more than 6,000. During this same period, more than 2,500 charter schools opened, and charter enrollment increased by nearly 2 million. This Catholic school crisis has many causes, of course, including the secularization and suburbanization of American Catholics; a dramatic decline in the number of religious sisters and priests, which has increased labor costs and tuitions; the lack of affinity for Catholic education among Latinos, who make up a majority of Catholics of childbearing age; resistance among some Church leaders to new models of school governance; and the clergy abuse scandal. Yet even with these factors considered, another important contributor has been a widespread belief among policymakers and education-reform advocates—but not necessarily parents, public-opinion polls suggest—that charters offer all the school choice we really need.

Since Minnesota enacted the first charter school law in 1991, charters have become the leading school-choice option for many reformers. The schools’ growing advantage has had profound implications for faith-based schools, which, unlike charters, can’t tap public funds—unless, that is, they secularize and become charters, as the Jubilee network has done. Charter schools are free, and parents of limited means, understandably, see them as reasonable substitutes for Catholic schools, which charge tuition. For many policymakers, the presence of charters as an option for low-income parents lessens or eliminates the need to give such parents the financial help they’d need to choose Catholic schools for their children. Even some Catholic leaders apparently assume that charters provide—or can be made to provide, if coupled with supplemental religious instruction—a substantially equivalent educational experience.

It’s time to rethink this compromise. Catholic schools provide a powerful education alternative for disadvantaged kids that charters can’t readily match. But their future viability—and that of other faith-based urban schools—will depend on the expansion of private school choice, broadly understood. Thankfully, momentum for private school choice is actually on the upswing: programs—including vouchers, tax-credit scholarship programs, and education-savings accounts—are now in place in more than half the states and the District of Columbia, and new initiatives launch yearly. If such efforts keep expanding, it may not be too late for Catholic schools to participate, with Espinoza clearing the way—and that would be a particular boon for the neediest students. But we need to reimagine the landscape of parental-choice policy to help make that happen.

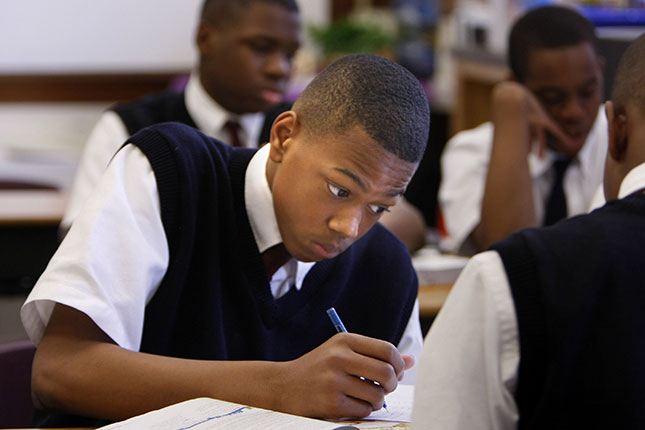

Urban Catholic schools have a long and noble record of helping to lift students out of poverty. Decades of social-science research have demonstrated a “Catholic school effect” on the academic performance and life outcomes of disadvantaged minority students. Beginning with the groundbreaking work of James Coleman and Andrew Greeley decades ago, scholars have found that Catholic school students—especially poor minorities—outperform their public school counterparts. More recently, Derek Neal’s research demonstrated that Catholic school attendance increased the likelihood that a minority student would graduate from high school from 62 percent to 88 percent and more than doubled the likelihood that a similar student would graduate from college. Catholic school students, controlling for a range of predictive demographic factors, are more likely to finish high school, attend college and graduate, maintain steady employment, and earn higher wages than similar students attending other types of schools.

Catholic schools are also especially good at forming citizens. A common argument against private school choice is that public schools are necessary to inculcate democratic values. The empirical evidence, however, suggests that private schools in general, and private schools participating in school-choice programs in particular, perform as well as, or better than, public schools in this task. For example, using data from the 1996 National Household Education Survey, my Notre Dame colleague David Campbell compared students enrolled in each educational setting along four variables: community service, “civic skills,” political knowledge, and political tolerance. Campbell found that private school students were significantly more likely to engage in community service, were better informed about the political process, and were, on average, more tolerant of political differences than students in public schools. Yet Campbell also discovered that the distinction between public and private schools vanished when Catholic schools were excluded from the analysis—leading him to conclude that “students in Catholic schools drive the private school effect.”

These results mirror those of other studies. In 2007, Patrick Wolf found that the effect of private schooling and school choice was almost always neutral or positive. “The statistical record shows that private schooling and school choice often enhance the realization of the civic values that are central to a well-functioning democracy,” he concluded. “This seems to be the case particularly . . . when Catholic schools are the schools of choice.”

Finally, urban Catholic schools help stabilize other community institutions. Margaret Brinig and I measured the effects of Catholic school closures on crime, perceived disorder, and perceived social cohesion in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. As reported in our book, Lost Classroom, Lost Community: Catholic Schools’ Importance in Urban America, we found that a Catholic school closure triggered a decrease in social capital and a rise in serious crime in urban neighborhoods. We also found that an open Catholic school appeared to suppress crime. Our analysis suggested that crime was, on average, at least 33 percent lower in Chicago police beats with open Catholic schools than in those with no such institutions. By contrast, we found that charter schools appeared to have no statistically significant effect on crime rates—though we don’t make causal claims about charter schools in this regard.

Charter schools have added valuable pluralism to the American education landscape, providing hope and opportunity to millions of children. Yet suggesting that they can replace what Catholic schools provide overlooks a stubborn fact: charters, by law, must be secular. While they can focus on curricular themes that appeal to people of certain faiths—for example, “classical” charters, or Hebrew- and Arabic-themed schools—the law prohibits them from teaching religion as the truth. When a Catholic school is “converted” into a charter, as in Memphis, the Catholic school closes and a new, distinct, and entirely secular institution takes its place. It is far from evident that secular schools can match the full range of benefits of urban Catholic education.

The fact that charter schools must be secular seems like a small price to pay for public funding, since many high-performing charters—especially those serving disadvantaged students—mimic some attributes of urban Catholic schools, including school uniforms, attention to discipline, and academic rigor. As Success Academy CEO and founder Eva Moskowitz once observed, charters are “Catholic on the outside.” But what if attending schools that are Catholic on the inside—precisely what charters cannot be, by law—really matters in the lives of young people? In a recent Manhattan Institute report, Kathleen Porter-Magee, superintendent of Partnership Schools, which operates nine Catholic schools in the Bronx, Harlem, and Cleveland, reflected on the “secret sauce” of Catholic education. As Porter-Magee observed, the culture and practices of Catholic schools incorporate distinctively Catholic elements. These include the belief in objective truth and an understanding that faith and reason are not incompatible; the conviction that all children—regardless of life circumstances—are formed in the image and likeness of a loving God and that Catholic educators have a duty to help them reach their God-given potential; an understanding that personal success and good character flow not only from obeying rules but also from cultivating good habits and virtue; and a conviction that God calls us to serve the common good, rather than simply maximize our individual achievement. These distinctive attributes of Catholic schools, rooted in faith and implemented by mission-driven teachers and educational leaders, may explain why Catholic schools’ long-term influence—as reflected in graduation rates, college persistence, and employment success—appears to eclipse that of some high-performing charter schools.

Charter schools are, technically speaking, privately operated public schools, created by an agreement—the “charter”—between a charter school operator and a government “authorizer.” Private organizations (usually nonprofits) manage the schools, which operate independently from local districts and are substantially freed from many regulations governing public schools.

Most charter students are racial minorities and come from disproportionately poor backgrounds. On the whole, the schools serve such students well. In 2015, for example, Stanford University’s Center for Research on Educational Opportunities studied charter schools in 41 regions and found that urban charter students demonstrated significantly higher levels of annual improvement in math and reading than their peers in traditional public schools. Disadvantaged minority students made the greatest gains.

Charter schools’ ascendancy is one of the most unexpected domestic policy developments of the last generation. Until 1991, none existed in the United States. Charters expanded rapidly after 1991, though, in part because, as secular public schools, they didn’t generate the same political opposition as vouchers. Indeed, until recently, charter schools were the bipartisan darlings of education reform. From their inception, they were endorsed as a modest alternative to vouchers, even by the two major teachers’ unions. President Barack Obama made charter schools a centerpiece of his education policy, as had Presidents George W. Bush and Bill Clinton. Forty-four states have authorized charters, about 7,500 exist nationwide, and approximately 6 percent of U.S. public school students—about 3.3 million children—attend one. And the charter market share is much higher in some urban districts. In the 2018–19 school year, in seven districts, more than 40 percent of public school students attended charters; more than 30 percent did in another 21 districts.

Yet the truce between charter advocates and supporters of traditional public schools has been breaking down. In July 2017, for instance, the National Education Association (the largest teachers’ union in the U.S.) amended its policy on charter schools, now characterizing them as a “failed experiment” and demanding that they be put under the control of local districts and permitted only when they don’t have an adverse impact on local traditional public schools. That same month, the NAACP called for a national moratorium on charters and decried their purported negative effects on traditional public schools—above all, those in urban areas. New charters face mounting regulatory scrutiny. Governor Gavin Newsom of California—the state with the largest number of charter students—pledged in his campaign to impose a moratorium on the schools, and he has signed legislation empowering districts to block new charters or the expansion of existing ones. Almost all the Democratic presidential hopefuls expressed hostility to charters, including Joe Biden, a previous supporter. And some opponents have recently gone so far as to accuse charter schools of being engines of systemic racism, despite their admirable record of helping minority students succeed.

Recent research shows that Catholic school attendance boosts the likelihood that a minority student will graduate from high school from 62 percent to 88 percent. (KAREN PULFER FOCHT/ZUMA PRESS, INC./NEWSCOM)

Recent research shows that Catholic school attendance boosts the likelihood that a minority student will graduate from high school from 62 percent to 88 percent. (KAREN PULFER FOCHT/ZUMA PRESS, INC./NEWSCOM)

Private school choice has a longer—and, at times, even more fraught—history. Its promise was to enlist existing schools with proven results in educating disadvantaged kids—especially urban Catholic schools—as publicly funded options for students in struggling public schools. But proponents of private school choice faced major political and legal hurdles, including the vehement resistance of teachers’ unions and significant constitutional uncertainty. The Supreme Court did not eliminate that uncertainty until 2002, when, in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, it rejected a federal Establishment Clause challenge to a voucher plan that allowed poor children in Cleveland to enroll in religious schools.

Since then, operating somewhat under the radar, private school–choice proponents have made inroads into state legislatures. Today, over half the states and the District of Columbia have at least one publicly funded private school–choice program, and participation in them has more than tripled over the last decade. The menu of choice options has expanded to include devices arguably less controversial than vouchers. Eighteen states have adopted scholarship tax-credit programs, which don’t directly fund scholarships but instead encourage donations to private scholarship organizations through tax policy. Six states have launched education-savings programs that empower parents to spend state education funds on a range of expenses, including private school tuition. All told, 55 private school–choice programs operate in the United States: 25 using vouchers, 22 scholarship tax credits, 6 education-savings accounts, and 2 individual tuition tax credits. The largest, measured by enrollment, are scholarship tax-credit plans in Arizona, Florida, and Pennsylvania and voucher systems in Indiana, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

Two key factors have fueled the momentum. First, the political coalition supporting choice has expanded and diversified as the arguments favoring private school choice have shifted from the rhetoric of markets and competition to the language of opportunity and fairness. As education scholar Terry Moe observes, “The modern arguments for vouchers have less to do with free markets than with . . . the commonsense notion that disadvantaged kids should never be forced to attend failing schools and that they should be given as many attractive options as possible.” Polls suggest that support for private school choice is now highest among disadvantaged and minority parents, who stand to gain the most from its expansion. Second, post-Zelman, state constitutional restrictions on funding religious schools have not proved insurmountable hurdles, as many commentators had predicted they would. These provisions are often referred to as Blaine Amendments, after Senator James G. Blaine of Maine, who unsuccessfully tried, in 1876, to amend the federal constitution to prohibit government funding of “sectarian” schools. As Justice Samuel Alito documents in his concurrence in Espinoza, the failed federal Blaine Amendment, as well as many of the state constitutional provisions modeled on it, was “prompted by virulent prejudice against immigrants, particularly Catholic immigrants.”

Thankfully, while state constitutional challenges inevitably follow the enactment of any new private school–choice program, they rarely succeed. In most states, Espinoza effectively precludes them altogether. In Espinoza, the Court held that the Montana Supreme Court violated the Free Exercise Clause when it relied on its own Blaine Amendment to invalidate a statute giving a $150 tax credit for contributions to an organization that provides scholarships to students who attend private schools. The Montana court had concluded that, because some of the participating students attended faith-based schools, the program violated the state’s Blaine Amendment, which forbids “any direct or indirect appropriation or payment” for “any sectarian purpose or to aid any church, school, academy . . . controlled in whole or in part by any church, sect, or denomination.” Montana acknowledged that the tax-credit program did not violate the federal Establishment Clause; but the state argued that it had an important interest in maintaining a greater degree of church-state separation than required by the federal constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court disagreed, holding that all discrimination against religious organizations is subject to the most exacting constitutional scrutiny and that Montana’s interest in enforcing its Blaine Amendment was not a compelling one. While questions about the scope of Espinoza’s holding will be tested in later litigation, the decision clears away, in many states, a major legal hurdle to expanding parental choice. (Espinoza eliminates a political hurdle as well, since Blaine Amendments are a bogeyman frequently trotted out by parental-choice opponents in legislative battles.)

Though parental-choice proponents have won many political battles—and, with Espinoza, a momentous legal one—the fact remains that many private school–choice initiatives are poorly designed, and all are more restricted in scope and eligibility than charter school programs. Eligibility is not universal, as it is with charter schools. Most programs are means-tested, and some are also limited to students attending failing schools. Others admit only students with disabilities, sometimes specific ones (e.g., autism, dyslexia). Many are small: in 2018, scholarship tax-credit programs in New Hampshire and Kansas enrolled just 416 and 369 students, respectively. Two hundred and fifty students used Mississippi’s Speech-Language Therapy Scholarship, and only 245 took advantage of Arkansas’s vouchers for disabled students.

Nor can private school choice compete with charters on a per-pupil funding basis. Vouchers do the best—averaging $5,848 per pupil, nearly double the $3,035 per-pupil average for scholarship tax-credit programs—but even including vouchers in the calculus, per-pupil allocations remain significantly lower than in charter schools (which, in turn, tend to receive less money than traditional public schools). It’s not surprising, therefore, that more than six times as many students currently attend charters (3.3 million) than participate in private school–choice plans (519,000).

It makes little sense for private school choice to be so limited. Hundreds of thousands of American children attend private schools with public assistance, while millions enroll in privately operated charter schools. State and federal laws consider charter schools “public,” but they function, for all practical purposes, as private schools, and perhaps—as several state and federal courts have ruled—for constitutional purposes as well. The Supreme Court has made clear that the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause does not preclude using public funds to enable children to attend faith-based schools, and it has just held that states’ anti-Establishment provisions can’t do so, either.

Any rethinking of the charter compromise must begin with how to achieve a more pluralistic parental-choice landscape. In an ideal world, we might reimagine U.S. education policy entirely. Most other Western industrial democracies (and many nations in the developing world) fund a broad range of schooling options, public and private. In Australia, all public and private schools (including faith-based institutions) receive funds according to the same per-pupil formula, calibrated to account for how schools serving more disadvantaged students need more money. In 2017, government funds covered over 70 percent of the recurrent fiscal costs of Catholic schools in Australia.

Two main paths exist to greater pluralism, neither necessarily exclusive of the other. The first would be to permit authentically faith-based charter schools by eliminating the legal requirements requiring charters to be secular. The second would be to expand the scope and scale of private school choice to allow more poor children to benefit. In the long term, following years of protracted litigation, the first option may become a reality. In the short term, the second course is both urgent and prudential.

In his dissent in Espinoza, Justice Stephen Breyer warns that the decision will lead to greater church/state entanglements and raises questions about complications in a number of hypothetical scenarios. One of Breyer’s questions: “What about charter schools?” To the extent that this question is now before us, Justice Breyer is right to raise it. A strong case can be made that religious charter schools are not prohibited by the First Amendment and may be required by it. All state and federal laws prohibit religious charter schools, and most prohibit religious institutions from operating them. It is reasonable to anticipate lawsuits challenging charter school laws on Free Exercise grounds. But the prospect of Catholic charter schools remains remote. Catholic schools cannot become Catholic charter schools until these laws are amended or successfully challenged in court. Some state legislators may introduce legislation permitting religious charter schools, but the current political fray over charters makes legislation authorizing more charters of any kind, let alone religious ones, difficult. Legislation for religious charters would face challenges, on state and federal constitutional grounds, and religious providers wishing to open new charters would probably be enjoined from doing so by lower courts, pending a Supreme Court resolution. This process might take years.

Litigation challenging the legal bans on faith-based charter schools also would be protracted, even if eventually successful. Meantime, Catholic schools serving disadvantaged kids would continue to close. Some Catholic leaders, facing a Hobson’s choice between secularizing their schools or going without public funding, will opt to secularize.

Thus, the current path of least resistance for those seeking to expand parental options to include faith-based schools is that of private school choice. After decades of lurking in the corners of state legislative halls and think tanks, choice has increasingly moved from the margins to the mainstream—and that trend should intensify. The resources provided to private school–choice programs should rise, to a level at least commensurate with charter funding. Congress is currently debating, and the Trump administration is strongly pushing, federal school-choice legislation in the wake of Covid-19. Florida recently expanded its private school–choice programs dramatically, opening the doors of private and faith-based schools to thousands more children. Other states should follow suit.

To accomplish the goal of a more pluralistic education system, parental-choice advocates and their legislative allies must attend more carefully to program design. For example, while scholarship tax credits may be less controversial politically, vouchers typically provide higher-value scholarships. Some scholarship tax-credit initiatives, such as Florida’s, work well, serving hundreds of thousands of children; others are ineffective. Education-savings accounts are theoretically appealing, but they have thus far proved relatively ineffectual because of confusion over access and qualifications. And virtually no existing choice program generates enough tuition revenue to motivate the opening of new schools where they’re needed. Faith-based schools should do their part here, embracing transparency and sharing information about their academic performance, accepting reasonable academic-accountability requirements, and, above all, demonstrating that parental choice works by providing a transformational education for disadvantaged students.

Private school–choice advocates should also build bridges with charter school proponents, who need political allies these days, and learn from their earlier successful expansion efforts. Charter schools began as a modest reform option and have had to overcome regulatory and performance obstacles to their growth. Many early laws dramatically limited the number of charter schools and placed geographic restrictions on their locations. Most also vested charter authorization authority solely in school districts, which were resistant to granting competitors permission to operate. After prominent studies suggested disappointing academic results, charter operators buckled down and demonstrated that they could provide high-quality education. Over time, networks of high-performing charter schools emerged. (Encouragingly, a handful of Catholic school networks serving poor children are also emerging, including the Notre Dame ACE Academies, New York’s Partnership Schools, the Philadelphia Mission Schools, and the Seton Catholic Schools in Milwaukee.) And charter school supporters have had to make regulatory compromises. For example, while most charters remain free to hire noncertified and nonunionized teachers, the federal Every Student Succeeds Act, enacted in 2015, requires the schools to participate fully in state educational-accountability regimes.

For some, especially those weary from legislative battles, the further expansion of parental choice may seem like a tall order. But victories in states with large Democratic majorities, including Illinois, where proponents thwarted efforts to gut the state’s scholarship tax-credit plan, suggest otherwise. And the daily stream of reports that yet another Catholic school has been forced to close for good by Covid-19 suggests that time is of the essence. The battle for parental choice, to be sure, is not for the fainthearted, but expanded choice is achievable—and should be pursued with urgency.